Each morning I start my ward round in the intensive care unit (ICU), where the sickest patients in the hospital are managed. Patients often get rushed into the ICU on the brink of death from the emergency department and from other wards, and the ICU team does its best to resuscitate and revive these children.

In ICU we usually have two nurses and one clinical officer (CO) around the clock, and a doctor who is onsite during the day, and on-call after hours. As doctors we cover multiple departments and wards, so it’s the COs and nurses who are with the patients 24-7.

COs are trained to work in a similar capacity to doctors, but their training is shorter than medical training, and more focused on pattern recognition. They are usually the first ones to see the patients, they make diagnoses and start treatment, they deliver bad news, they run resuscitations and perform procedures. They truly are the backbone of the Aweil MSF hospital.

On this particular day, I walk into the ICU to find the CO with a patient on the resuscitation bed. Deng* is a seven-year-old boy who has been admitted with cerebral malaria and intractable seizures. He was given diazepam and phenytoin in the ER, and is now gasping, his oxygen saturation level is low and his heart rate low. This is becoming a familiar sight: a patient who is about to arrest. Maybe it’s from the cerebral malaria, maybe it’s from the medications given to stop seizures—we cannot be sure. We make the decision to start ventilating with the manual resuscitation device known as a bag-mask.

Stories from South Sudan: Lives in the balance

In this third and final part of her blog series from Aweil, South Sudan, Dr Madeleine Finney-Brown describes an unforgettable day in the paediatric Intensive Care Unit.

An MSF-commissioned painting in Aweil’s market area to promote blood donations and ensure the availability of blood transfusions for the many patients needing them during the malaria peak. © Madeleine Finney-Brown

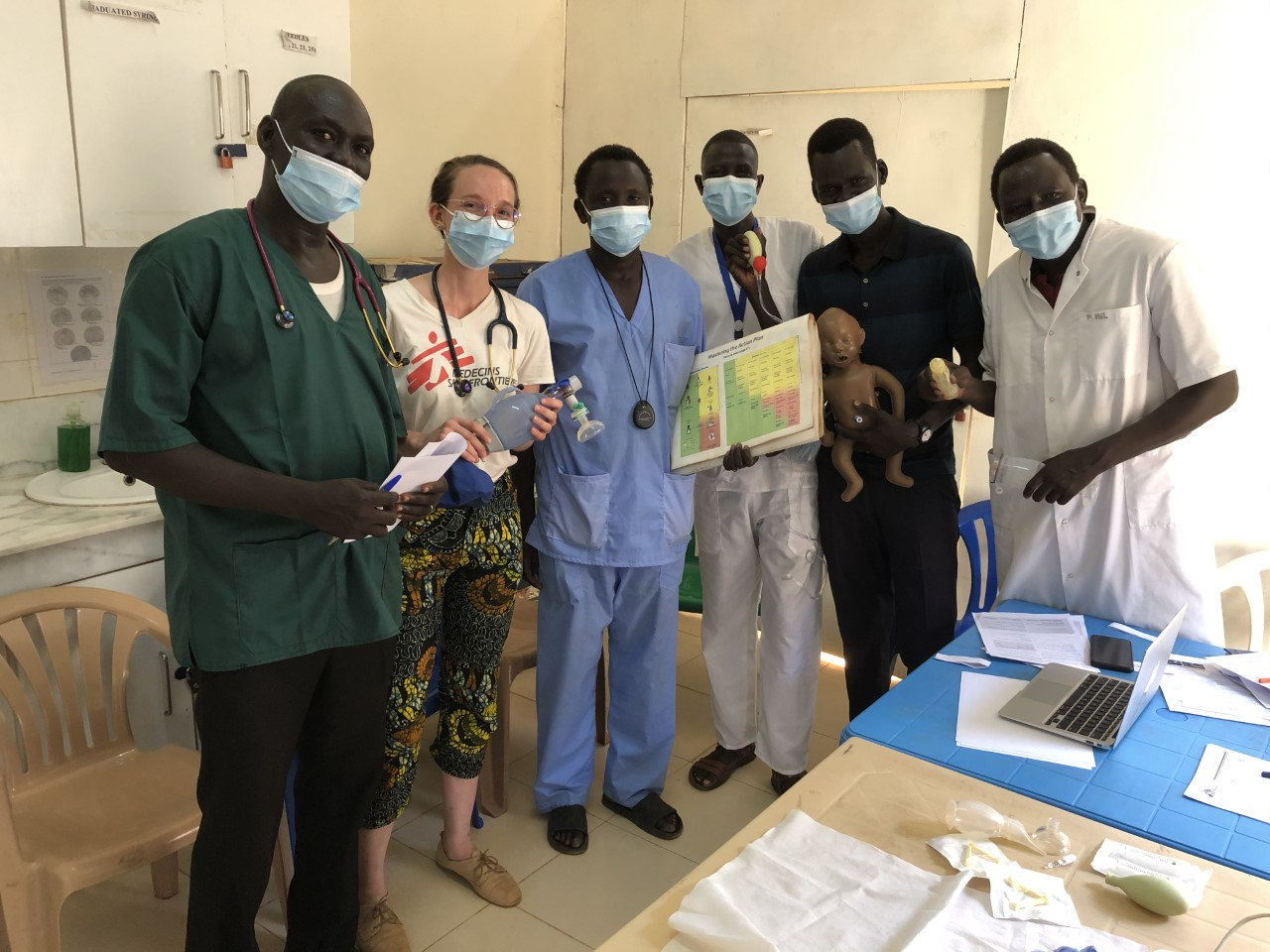

Dr Madeleine Finney-Brown assisting national doctor Dr Mel Simon (far right) with neonatal resuscitation training in Aweil, South Sudan, from left to right: Clinical Officer Dominic Deng Piol, nurse aide Benson Muorter Dau, nurse Teng Barnabas Rual and midwife William Yai Atem. © Deng Garang Nyeng

Shortly after my CO colleague starts ventilating, Deng stops breathing. His oxygen saturation and heart rate thankfully come up as he is being manually ventilated. However, he is still not breathing on his own, meaning that Deng’s life is literally in the hands of my colleague. We don’t have a machine to do this, nor do we have the staffing capacity to allow one person to continue to ventilate for an extended period of time.

We have been ventilating Deng for almost 20 minutes and still he’s not breathing. I ask the interpreter to help me have the hardest of conversations with his mother, who has been watching anxiously. “Your boy is not breathing on his own... we’ve done all that we can, but it might not be enough. I’m so sorry.” I finish by asking her if she has any questions. “Yes,” she responds in Dinka, "Can we pray?” I’m taken aback—it’s not the response I was expecting. “Of course,” I reply. And pray she does. I am not religious, but it was such a powerful, tragically beautiful moment. One that I hope never to forget.

Imagine this scene: a Wednesday morning in our humble yet chaotic ICU. All nine beds are occupied with the sickest patients in the hospital. In the bed next to the door is a baby with meningitis who hasn’t woken up, and may never. Next to her is a nine-month-old girl with Down Syndrome and pneumonia, who gasps for each breath, as her mother rocks her gently. Her neighbour is a 12-year-old boy who was bitten by a snake not once, but twice: one bite on each leg. It took two days for him to reach hospital. By that time, had already developed gangrene in his left leg, which is planned for amputation. We’re all hoping the swelling will reduce in his other leg so that at least one leg can be saved.

“Your boy is not breathing on his own... we’ve done all that we can, but it might not be enough. I’m so sorry.”

Across from him is a one-month-old baby who we thought had pneumonia, but an ultrasound of her heart has revealed a structural defect that is a death sentence unless her family can afford to travel to Khartoum for surgery. Her mother never kisses her just once, always four times: one, two, three, and four. The next two beds are occupied by children with cerebral malaria, both in deep comas. We are uncertain if they will recover. There’s a six-month-old who has severe acute malnutrition and has come in with diarrhoea and a chest infection. His skeletal frame lies listlessly on the bed; with each breath his ribs become all the more prominent, and the mere act of breathing takes up all of his energy.

And in the corner is a 15-year-old boy who has type 1 diabetes and epilepsy who is frequently in hospital with the complication known as diabetic ketoacidosis, from not taking his insulin. This time he also has malaria, and he is confused.

Doctor Mel Simon (in white) demonstrates how to perform CPR on a baby whilst midwife William Yai Atem practises ventilation and Clinical Officer Dominic Deng Piol looks on, as part of a newborn resuscitation training session run by Dr Mel Simon in Aweil, South Sudan. © Madeleine Finney-Brown.

Imagine all of this. The noise of infusion pumps, oxygen concentrators, a baby crying, the moans of a confused teenager, someone’s mobile phone ringing, the ceiling fan squeaking with each turn, and the rumble of the generator off in the distance.

And then Deng’s mother starts singing a hymn, melodic and emotional. Her faith, her love, her strength wrapped up in each note. She is accompanied by the cacophony of noises from the ward, and the rhythmic compression of the bag-mask signalling each breath given to her son. We reach 40 minutes of ventilation and we really need to stop. One of the nurses places an oxygen mask on Deng’s face and we all wait with bated breath. His mother’s prayer intensifies. The seconds stretch as we watch and wait, and then... a gasp. And another. He starts breathing on his own. Sighs of relief all around.

But now the next challenge: as his conscious state improves, his seizures return. One after another. We start more medication. All day he is unconscious, seizing often. He’s too far gone, I think to myself as I leave that evening. The malaria is too severe.

The next morning I am delighted to see this same boy awake, albeit a little bit grumpy. He can’t yet sit on his own, so his mother helps him sit whilst feeding him porridge. We grin at each other—the universal language. “I want to go home,” he says to his mother. You will very soon, my friend!

*The patient’s name has been changed to provide privacy.