Our field workers have been, and continue to be, leaders in MSF’s response to humanitarian crises around the world – and their stories honour the voices of those we serve: our patients.

25 years of Australian and New Zealand humanitarianism

Australian and New Zealand field workers have made an amazing contribution over the 25 years since Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) Australia was established.

Dr Nicole Gilroy, the first field worker recruited by MSF Australia, on assignment in a refugee camp in Burundi, 1994. © MSF

In 1994, MSF remained in Kigali, Rwanda, throughout the genocide of more than 800,000 people, and made the unprecedented decision to call for international military intervention. MSF teams – including our first Australian-recruited field worker, Dr Nicole Gilroy – also worked in Burundi, extending assistance to Burundians repatriated from Rwanda.

“We were there to build a residential tuberculosis clinic, a straightforward enough job on paper but a logistical nightmare in reality. Organising a building project in an environment with no infrastructure (no water, no electricity, limited supplies and a low skill base) is a challenge at the best of times, but to discover the site was on a former battlefield complicated things beyond our wildest expectations. Clearing a site of landmines and UXO (unexploded ordnance), unearthing an anti-tank mine and a rocket, were simply things that hadn’t been part of our initial game plan.” Logistician Grant Somers, from Sydney, remembers the challenges of his first field assignment in Ghazni, Afghanistan, 2001. © Grant Somers / MSF

An MSF staff member attends to a child in the nutrition centre of the HIV/AIDS program in Chiradzulu, Malawi, 2002. © Isabelle Merny / MSF

“After the tsunami in Aceh, MSF conducted an assessment of basic material needs and we were subsequently able to distribute necessary items such as blankets, cooking utensils and clothing. We also facilitated and restored community activities such as soccer games, playgroups for children and public meetings where people can share their experiences and ways of coping.

“In Aceh, I held weekly meetings over three months with a Muslim women’s group. Discussions included grounding techniques (for coping with dissociation related to flashbacks), dealing with children’s nightmares, grief issues and shared problem solving.”

- Malcolm Hugo, a psychologist from Adelaide, reflects on responding to the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami in Banda Aceh, Indonesia. Australians donated more than $1 million within 36 hours to the cause – exceeding the estimated cost of an operational response to the tsunami, and leading MSF Australia to make the unprecedented decision to close its fundraising appeal to help focus donations back to other crises. © MSF

A mother feeds her child with ‘Plumpy’Nut’, a therapeutic food, in a camp for internally displaced people in Darfur, Sudan, 2008. © Anne Yzebe / MSF

“When I see a desperately sick kid come into the hospital, on the verge of death, and see the worried face of the mother as she hovers helplessly around the bed while the doctors and nurses treat her child, I know that we will all do our best, just for that mother and child.

“The result isn't always happy, but when, three weeks, a month, or six months later, that mother and her child walk out of the hospital, I know that everyone – from the doctors and nurses who looked after them, to the logisticians who made sure the oxygen was working, to the cleaner who swept the floor, and all the way back to the office staff in Sydney who sent us to the field and the generous donors who make our work possible – contributed to the health of that child.

“And while we may not be able to save the world, we saved the life of that one child, and for that mother, we saved her flesh and blood, her world. And that is a joy that is impossible to replicate. This is the most rewarding job I can imagine.”

– Damien Moloney, from Melbourne, on working as a logistician during 12 field placements with MSF. © MSF

"Over the last four weeks, we have admitted over a hundred people to the hospital for dehydration, infection or severe malnutrition. We’ve had women getting off buses already in labour, people with malaria, lots of people who need hospital-level 24-hour care to simply secure their survival.

“Within this culture, it’s not always easy for women to make decisions in these circumstances. Some evenings, I’ve talked to women about bringing their sick child to the hospital and they say they have to wait until their husband arrives. In those cases, we do what we can to provide immediate health care on the spot until someone can make that decision to bring the child to hospital.

“We’re meeting this community for the first time, so we have to be patient and try to understand their needs. What we might see as a priority is not necessarily the same for the family; that’s part of this new relationship we’re trying to develop."

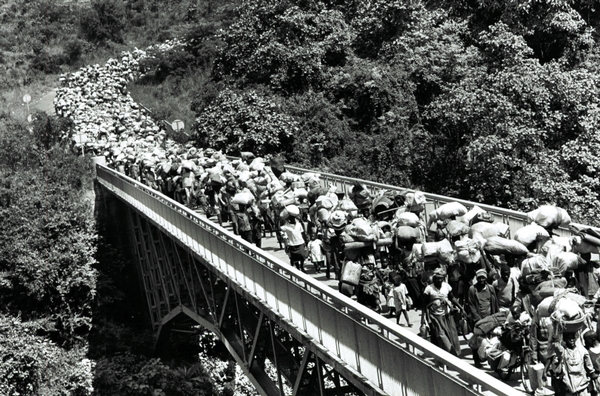

- Vanessa Cramond, a nurse from Auckland, writes from the 2012 refugee crisis in South Sudan, where she worked as medical coordinator with people who had crossed into Maban County after fleeing fighting in Sudan’s Blue Nile state. © Corinne Baker / MSF

“Here were people who had lost everything, but they still offered us food and what was left of their homes.”

– Gandhi Pant, a nurse from Bathurst, NSW, worked as part of the MSF emergency team that provided healthcare to people in remote mountainous areas of Nepal after the 2015 earthquake. © MSF

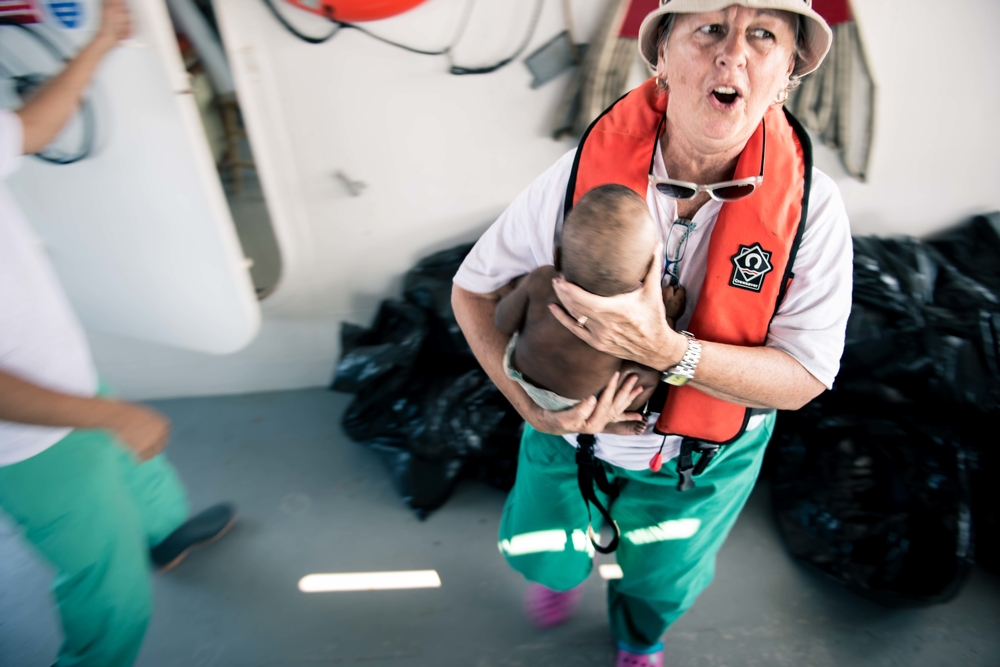

“It is an incredible yet tragic situation to witness… thousands of desperate people risking their lives – at times, their entire family – to escape from intolerable conditions. On one day in the Mediterranean our small medical team of six rescued 1,000 people who were on three separate leaking vessels (two inflatable dinghies and one wooden fishing boat) from perishing at sea.

“It is very sad to realise that many of us living comfortable, safe lives have a sense of fear and suspicion toward these people, and that many governments play on these fears to avoid responding in a humanitarian way.”

– Carol Nagy, from Hobart, reflects on assisting people making the dangerous journey from Africa to Europe, while placed with the MSF joint search, rescue and medical operation in the Central Mediterranean, 2015. © Gabriele François Casini / MSF

A young boy recovers in the MSF clinic in Kutupalong camp, in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, September 2017. © Antonio Faccilongo / MSF

“Yesterday was tough. Sadly, we lost a very kind young man despite the incredibly compassionate care our team provided.

“But, thankfully, some wonderful news today with one of our patients being cured – cause for celebration indeed! The first patient who was discharged as cured from our unit was Mwamini. The literal translation of her name is ‘faith’. When she heard the news, Mwamini broke into song and dance. Our hardworking team and two fellow patients joined in to celebrate this most joyous moment.

“Mwamini is an incredible inspiration to our whole team and has continued my faith in humanity. This has touched my heart forever.”

– Dr Saschveen Singh, from Perth, shares a story of hope from the ongoing Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo. © John Wessels / MSF

A young patient, injured by a mortar explosion, speaks with relatives in a MSF field trauma clinic in Iraq, 2017. Ó Alice Martins / MSF

The MSF mental health team attends to a patient on Nauru in 2018. © MSF

MSF field staff worldwide provide lifesaving medical and technical assistance to people who would otherwise be denied access to basics such as healthcare, clean water, and shelter. Find out more about becoming a field worker here.